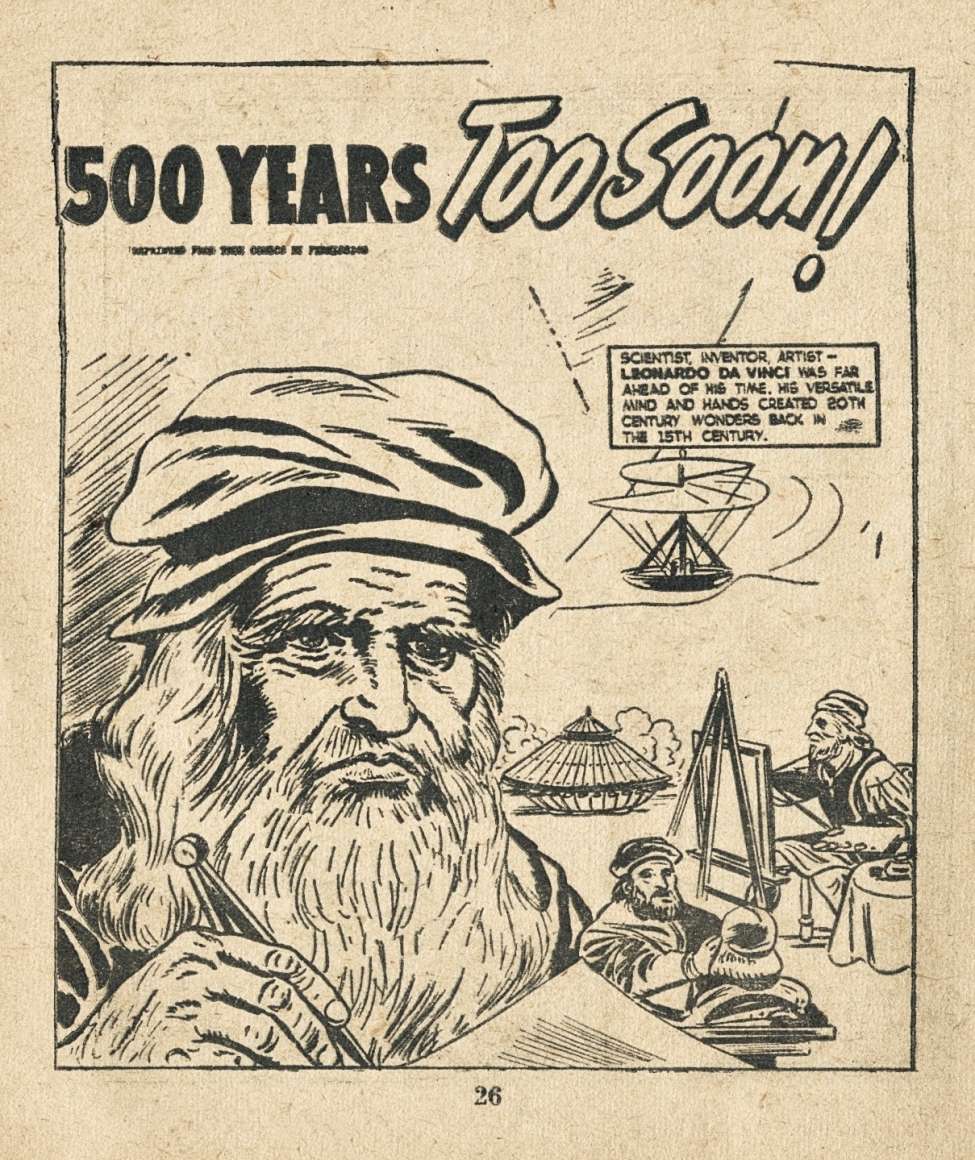

Most people with any knowledge or interest in early attempts at human-powered flight are familiar with the works of

Leonardo Da Vinci and His Flying Machines, the famous fifteenth century renaissance artist and inventor. The question arises though, did the Da Vinci machines actually work, that is, fly successfully approximately four-hundred years before anybody else was able to accomplish the task? That is a question that has been debated for decades. There is no clear hard-core evidence that specifically states yes, however, if one goes over the material by Leonardo and his contemporaries one can cull out some rather interesting facts that attest to the fact that YES his machines did work and Leonardo did fly.

Leonardo's First Flight

The Great Bird was perched on the edge of a ridge at the summit of a hill near Vinci that Leonardo had selected, its fabric of fustian and silk sighing and the expansive wings shifting slightly in the wind. Niccolo, Tista, and Leonardo's stepfather Achattabrigha kneeled under the wings and held fast to the pilot's harness. Zoroastro da Peretola and Lorenzo de Credi, apprentices of Andrea Verrochio, stood twenty-five feet apart and steadied the wing tips; it almost seemed that their arms were filled with outsized jousting pennons of blue and gold. These two could be taken as caricatures of Il Magnifico and his brother Giuliano, for Zoroastro was swarthy, rough- skinned, and ugly-looking beside the sweetly handsome Lorenzo de Credi. Such was the contrast between Lorenzo and Giuliano di Medici, who stood with Leonardo a few feet away from the Great Bird. Giuliano looked radiant in the morning sun while Lorenzo seemed to be glowering, although he was most probably simply concerned for Leonardo.

Zoroastro, ever impatient, looked toward Leonardo and shouted, "We're ready for you, Maestro."

Leonardo nodded, but Lorenzo caught him and said, "Leonardo, there is no need for this. I will love you as I do Giuliano, no matter whether you choose to fly...or let wisdom win out."

Leonardo smiled and said, "I will fly fide et amore."

By faith and love.

"You shall have both," Lorenzo said; and he walked beside Leonardo to the edge of the ridge and waved to the crowd standing far below on the edge of a natural clearing where Leonardo was to land triumphant. But the clearing was surrounded by a forest of pine and cypress, which from his vantage looked like a multitude of rough- hewn lances and halberds. A great shout went up, honoring the First Citizen: the entire village was there—from peasant to squire, invited for the occasion by Il Magnifico, who had erected a great, multi-colored tent; his attendants and footmen had been cooking and preparing for a feast since dawn. His sister Bianca, Angelo Poliziano, Pico Della Mirandola, Bartolomeo Scala, and Leonardo's friend Sandro Botticelli were down there, too, hosting the festivities.

They were all on tenterhooks, eager for the Great Bird to fly.

Leonardo waited until Lorenzo had received his due; but then not to be outdone, he, too, bowed and waved his arms theatrically. The crowd below cheered their favorite son, and Leonardo turned away to position himself in the harness of his flying machine. He had seen his mother Caterina, a tiny figure nervously looking upward, whispering devotions, her hand cupped above her eyes to cut the glare of the sun. His father Piero stood beside Giuliano de Medici; both men were dressed as if for a hunt. Piero did not speak to Leonardo. His already formidable face was drawn and tight, just as if he were standing before a magistrate awaiting a decision on a case.

Lying down in a prone position on the fore-shortened plank pallet below the wings and windlass mechanism, Leonardo adjusted the loop around his head, which controlled the rudder section of the Great Bird, and he tested the hand cranks and foot stirrups, which raised and lowered the wings.

"Be careful," shouted Zoroastro, who had stepped back from the moving wings. "Are you trying to kill us?"

There was nervous laughter; but Leonardo was quiet. Achattabrigha tied the straps that would hold Leonardo fast to his machine and said, "I shall pray for your success, Leonardo, my son. I love you."

Leonardo turned to his step-father, smelled the good odors of Caterina's herbs—garlic and sweet onion—on his breath and clothes, and looked into the old man's squinting, pale blue eyes; and it came to him then, with the force of buried emotion, that he loved this man who had spent his life sweating by kiln fires and thinking with his great, yellow-nailed hands. "I love you, too...father. And I feel safe in your prayers."

That seemed to please Achattabrigha, for he checked the straps one last time, kissed Leonardo and patted his shoulder; then he stepped away, as reverently as if he were backing away from an icon in a cathedral.

"Good luck, Leonardo," Lorenzo said.

The others wished him luck. His father nodded, and smiled; and Leonardo, taking the weight of the Great Bird upon his back, lifted himself. Niccolo, Zoroastro, and Lorenzo de Credi helped him to the very edge of the ridge.

A cheer went up from below.

"Maestro, I wish it were me," Niccolo said. Tista stood beside him, looking longingly at Leonardo's flying mechanism.

"Just watch this time, Nicco," Leonardo said, and he nodded to Tista. "Pretend it is you who is flying in the heavens, for this machine is also yours. And you will be with me."

"Thank you, Leonardo."

"Now step away...for we must fly," Leonardo said; and he looked down, as if for the first time, as if every tree and upturned face were magnified; every smell, every sound and motion were clear and distinct. In some way the world had separated into its component elements, all in an instant; and in the distance, the swells and juttings of land were like that of a green sea with long, trailing shadows of brown; and upon those motionless waters were all the various constructions of human habitations: church and campanile, and shacks and barns and cottages and furrowed fields.

Leonardo felt sudden vertigo as his heart pounded in his chest. A breeze blew out of the northwest, and Leonardo felt it flow around him like a breath. The treetops rustled, whispering, as warm air drifted skyward. Thermal updrafts flowing invisibly to heaven. Pulling at him. His wings shuddered in the gusts; and Leonardo knew that it must be now, lest he be carried off the cliff unprepared.

He launched himself, pushing off the precipice as if he were diving from a cliff into the sea. For an instant, as he swooped downward, he felt euphoria. He was flying, carried by the wind, which embraced him in its cold grip. Then came heart-pounding, nauseating fear. Although he strained at the windlass and foot stirrups, which caused his great, fustian wings to flap, he could not keep himself aloft. His pushings and kickings had become almost reflexive from hours of practice: one leg thrust backward to lower one pair of wings while he furiously worked the windlass with his hands to raise the other, turning his hands first to the left, then to the right. He worked the mechanism with every bit of his calculated two hundred pound force, and his muscles ached from the strain. Although the Great Bird might function as a glider, there was too much friction in the gears to effect enough propulsive power; and the wind resistance was too strong. He could barely raise the wings.

He fell.

The chilling, cutting wind became a constant sighing in his ears. His clothes flapped against his skin like the fabric of his failing wings, while hills, sky, forest, and cliffs spiraled around him, then fell away; and he felt the damp shock of his recurring dream, his nightmare of falling into the void.

But he was falling through soft light, itself as tangible as butter. Below him was the familiar land of his youth, rising against all logic, rushing skyward to claim him. He could see his father's house and there in the distance the Apuan Alps and the ancient cobbled road built before Rome was an empire. His sensations took on the textures of dream; and he prayed, surprising himself, even then as he looked into the purple shadows of the impaling trees below. Still, he doggedly pedaled and turned the windlass mechanism.

All was calmness and quiet, but for the wind wheezing in his ears like the sea heard in a conch shell. His fear left him, carried away by the same breathing wind.

Then he felt a subtle bursting of warm air around him.

And suddenly, impossibly, vertiginously, he was ascending.

His wings were locked straight out. They were not flapping. Yet still he rose. It was as if God's hand were lifting Leonardo to Heaven; and he, Leonardo, remembered loosing his hawks into the air and watching them search for the currents of wind, which they used to soar into the highest of elevations, their wings motionless.

Thus did Leonardo rise in the warm air current—his mouth open to relieve the pressure constantly building in his ears—until he could see the top of the mountain...it was about a thousand feet below him. The country of hills and streams and farmland and forest had diminished, had become a neatly patterned board of swirls and rectangles: proof of man's work on earth. The sun seemed brighter at this elevation, as if the air itself was less dense in these attenuated regions. Leonardo feared now that he might be drawing too close to the region where air turned to fire.

Leonardo Da Vinci: Bird's-Eye View of a Landscape. 1502.

Pen, ink and watercolor on paper. Windsor Castle, Windsor, UK

He turned his head, pulling the loop that connected to the rudder; and found that he could, within bounds, control his direction. But then he stopped soaring; it was as if the warm bubble of air that had contained him had suddenly burst. He felt a chill.

The air became cold...and still.

He worked furiously at the windlass, thinking that he would beat his wings as birds do until they reach the wind; but he could not gain enough forward motion.

Once again, he fell like an arcing arrow.

Although the wind resistance was so great that he couldn't pull the wings below a horizontal position, he had developed enough speed to attain lift. He rose for a few beats, but, again, could not push his mechanism hard enough to maintain it, and another gust struck him, pummeling the Great Bird with phantomic fists.

Leonardo's only hope was to gain another warm thermal.

Instead, he became caught in a riptide of air that was like a blast, pushing the flying machine backward. He had all he could do to keep the wings locked in a horizontal position. He feared they might be torn away by the wind; and, indeed, the erratic gusts seemed to be conspiring to press him back down upon the stone face of the mountain.

Time seemed to slow for Leonardo; and in one long second he glimpsed the clearing surrounded by forest, as if forming a bull's-eye. He saw the tents and the townspeople who craned their necks to goggle up at him; and in this wind-wheezing moment, he suddenly gained a new, unfettered perspective. As if it were not he who was falling to his death.

Were his neighbors cheering? he wondered. Or were they horrified and dumbfounded at the sight of one of their own falling from the sky? More likely they were secretly wishing him to fall, their deepest desires not unlike the crowd that had recently cajoled a poor, lovesick peasant boy to jump from a rooftop onto the stone pavement of the Via Calimala.

The ground was now only three hundred feet below.

To his right, Leonardo caught sight of a hawk. The hawk was caught in the same trap of wind as Leonardo; and as he watched, the bird veered away, banking, and flew downwind. Leonardo shifted his weight, manipulated the rudder, and changed the angle of the wings. Thus he managed to follow the bird. His arms and legs felt like leaden weights, but he held on to his small measure of control.

Still he fell.

Two hundred feet.

He could hear the crowd shouting below him as clearly as if he were among them. People scattered, running to get out of Leonardo's way. He thought of his mother Caterina, for most men call upon their mothers at the moment of death.

And he followed the hawk, as if it were his inspiration, his own Beatrice.

And the ground swelled upward.

Then Leonardo felt as if he was suspended over the deep, green canopy of forest, but only for an instant. He felt a warm swell of wind; and the Great Bird rose, riding the thermal. Leonardo looked for the hawk, but it had disappeared as if it had been a spirit, rising without weight through the various spheres toward the Primum Mobile. He tried to control his flight, his thoughts toward landing in one of the fields beyond the trees.

The thermal carried him up; then, just as quickly, as if teasing him, burst. Leonardo tried to keep his wings fixed, and glided upwind for a few seconds. But a gust caught him, once again pushing him backward, and he fell—

Leonardo had suffered several broken ribs and a concussion when he fell into the forest, swooping between the thick, purple cypress trees, tearing like tissue the wood and fustaneum of the Great Bird's wings. His face was already turning black when Lorenzo's footmen found him. He recuperated at his father's home; but Lorenzo insisted on taking him to Villa Careggi, where he could have his physicians attend to him. With the exception of Lorenzo's personal dentator, who soaked a sponge in opium, morel juice, and hyoscyamus and extracted his broken tooth as Leonardo slept and dreamed of falling, they did little more than change his bandages, bleed him with leeches, and cast his horoscope.

Leonardo was certain that the dreams would cease only when he conquered the air; and although he did not believe in ghosts or superstition, he was pursued by demons every bit as real as those conjured by the clergy he despised and mocked. So he worked, as if in a frenzy. He constructed new models and filled up three folios with his sketches and mirror-script notes. Niccolo and Tista would not leave him, except to bring him food, and Andrea Verrocchio came upstairs a few times a day to look in at his now famous apprentice.

"Haven't you yet had your bellyful of flying machines?" Andrea impatiently asked Leonardo. It was dusk, and dinner had already been served to the apprentices downstairs. Niccolo hurried to clear a place on the table so Andrea could put down the two bowls of boiled meat he had brought. Leonardo's studio was in its usual state of disarray, but the old flying machine, the insects mounted on boards, the vivisected birds and bats, the variously designed wings, rudders, and valves for the Great Bird were gone, replaced by new drawings, new mechanisms for testing wing designs for now the wings would remain fixed.

"You are lucky to be alive, Leonardo. Have you not looked at yourself in a mirror? And you nearly broke your spine. Are you so intent upon doing so again? Or will killing yourself suffice?" He shook his head, as if angry at himself. " You've become skinny as a rail and sallow as an old man. Do you eat what we bring you? Do you sleep?" Do you paint? No, nothing but invention, nothing but...this." He waved his arm at the models and mechanisms that lay everywhere. Then in a soft voice, he said, "I blame myself. I should have never allowed you to proceed with all this in the first place. You need a strong hand."

"When Lorenzo sees what I have—"

The Second Flight

Leonardo stood and stared down the mountain side to the valley below. Mist flowed dreamlike down its grassy slopes; in the distance, surrounded by grayish-green hills was Florence, its Duomo and the high tower of the Palazzo Vecchio golden in the early sunlight. It was a brisk morning in early March, but it would be a warm day. The vapor from Leonardo's exhalations was faint. He had come here to test the Da Vinci Glider, which now lay nearby, its large, arched wings lashed to the ground. This flying machine had fixed wings and no hand-powered motor. It was a glider. His plan was to master flight; when he developed a suitable engine to power his craft, he would then know how to control it. And this machine was more in keeping with Leonardo's ideas of nature, for he would wear the wings, as if he were, indeed, a bird; he would hang from the wings, legs below, head and shoulders above, and control them by swinging his legs and shifting his weight. He would be like a bird soaring, sailing, gliding.

But he had put off flying the contraption for the last two days that they had camped here. Even though he was certain that its design was correct, he had lost his nerve. He was afraid. He just could not do it.

But he had to....

He could feel Niccolo and Tista watching him.

He kicked at some loamy dirt and decided: he would do it now. He would not think about it. If he was to die...then so be it. Could being a coward be worse than falling out of the sky?

But he was too late, too late by a breath.

Niccolo shouted.

Startled, Leonardo turned to see that Tista had torn loose the rope that anchored the glider to the ground and had pulled himself through the opening between the wings. Leonardo shouted "stop" and rushed toward him, but Tista threw himself over the crest before either Leonardo or Niccolo could stop him. In fact, Leonardo had to grab Niccolo, who almost fell from the mountain in pursuit of his friend.

Tista's cry carried through the chill, thin air, but it was a cry of joy as the boy soared through the empty sky. He circled the mountain, catching the warmer columns of air, and then descended.

"Come back," Leonardo shouted through cupped hands, yet he could not help but feel an exhilaration, a thrill. The machine worked! But it was he, Leonardo, who needed to be in the air.

"Maestro, I tried to stop him," Niccolo cried.

But Leonardo ignored him, for the weather suddenly changed, and buffeting wind began to whip around the mountain. "Stay away from the slope," Leonardo called. But he could not be heard; and he watched helplessly as the glider pitched upwards, caught by a gust. It stalled in the chilly air, and then fell like a leaf. "Swing your hips forward," Leonardo shouted. The glider could be brought under control. If the boy was practiced, it would not be difficult at all. But he wasn't, and the glider slid sideways, crashing into the mountain.

Niccolo screamed, and Leonardo discovered that he, too, was screaming.

Tista was tossed out of the harness. Grabbing at brush and rocks, he fell about fifty feet.

By the time Leonardo reached him, the boy was almost unconscious. He lay between two jagged rocks, his head thrown back, his back twisted, arms and legs akimbo.

"Where do you feel pain?" Leonardo asked as he tried to make the boy as comfortable as he could. There was not much that could be done, for Tista's back was broken, and a rib had pierced the skin. Niccolo kneeled beside Tista; his face was white, as if drained of blood.

"I feel no pain, Maestro. Please do not be angry with me." Niccolo took his hand.

"I am not angry, Tista. But why did you do it?"

"I dreamed every night that I was flying. In your contraption, Leonardo. The very one. I could not help myself. I planned how I would do it." He smiled wanly. "And I did it."

"That you did," whispered Leonardo, remembering his own dream of falling. Could one dreamer effect another?

"Niccolo...?" Tista called in barely a whisper.

"I am here."

"I cannot see very well. I see the sky, I think."

Niccolo looked to Leonardo, who could only shake his head.

When Tista shuddered and died, Niccolo began to cry and beat his hands against the sharp rocks, bloodying them. Leonardo embraced him, holding his arms tightly and rocking him back and forth as if he were a baby. All the while he did so, he felt revulsion; for he could not help himself, he could not control his thoughts, which were as hard and cold as reason itself.

Although his flying machine had worked—or would have worked successfully, if he, Leonardo, had taken it into the air—he had another idea for a great bird.

One that would be safe.

As young Tista's inchoate soul rose to the heavens like a kite in the wind, Leonardo imagined just such a machine.

A child's kite....

"Leonardo, why are you afraid?" Niccolo asked. "The machine...worked. It will fly."

"And so you wish to fly it, too? Leonardo asked, but it was more a statement than a question; he was embarrassed and vexed that Niccolo would demean him in front of Verrochio.

But, indeed, the machine had worked.

The Third Flight

But this flying machine he imagined was like no other device he had ever sketched or built. He had reached beyond nature to conceive a child's kite with flat surfaces to support it in the still air. It would have double wings, cellular open-ended boxes that would be as stable as kites of like construction.

Stable...and safe.

The pilot would not need to shift his balance to keep control. He would float on the air like a raft. Tista would not have lost his balance and fallen out of the sky in this contraption.

A LATER 19 th CENTURY FLYING MACHINE,- A VIRTUAL

COPY OF A FLORENCE DA VINCI GLIDER. CLICK IMAGE

TO SEE PILOT IN LOWER WING CENTER "FLOATING ON

THE AIR LIKE A RAFT"

"Tell Lorenzo that I'll have a soaring machine ready to impress the archbishop when he arrives," Leonardo said. "But he's not due for a fortnight."

"You've taken too long already." Sandro Botticelli stood in Leonardo's new studio, which was small and in disarray; although the roof had been repaired, Leonardo did not want to waste time moving back into his old room. Sandro was dressed as a dandy, in red and green, with dags and a peaked cap pulled over his thick brown hair. It was a festival day, and the Medici and their retinue would take to the streets for the Palio, the great annual horse race. "Lorenzo sent me to drag you to the Palio, if need be."

"If Andrea had allowed Francesco to help me—or at least lent me a few apprentices—I would have it finished by now."

"That's not the point."

"That's exactly the point."

"Get out of your smock; you must have something that's not covered with paint and dirt."

"Come, I'll show you what I've done," Leonardo said. "I've put up canvass outside to work on my soaring machine. It's like nothing you've ever seen, I promise you that. I'll call Niccolo, he'll be happy to see you."

"You can show it to me on our way, Leonardo. Now get dressed. Niccolo has left long ago."

"What?"

"Have you lost touch with everyone and everything?" Sandro asked. "Niccolo is at the Palio with Andrea...who is with Lorenzo. Only you remain behind."

"But Niccolo was just here."

Sandro shook his head. "He's been there for most of the day. He said he begged you to accompany him."

"Did he tell that to Lorenzo, too?"

"I think you can trust your young apprentice to be discreet."

Dizzy with fatigue, Leonardo sat down by a table covered with books and models of kites and various incarnations of his soaring machine. "Yes, of course, you're right, Little Bottle."

"You look like you've been on a binge. You've got to start taking care of yourself, you've got to start sleeping and eating properly. If you don't, you'll lose everything, including Lorenzo's love and attention. You can't treat him as you do the rest of your friends. I thought you wanted to be his master of engineers."

"What else has Niccolo been telling you?"

Sandro shook his head in a gesture of exasperation, and said, "Change your clothes, dear friend. We haven't more than an hour before the race begins."

"I'm not going," Leonardo said, his voice flat. "Lorenzo will have to wait until my soaring machine is ready."

"He will not wait."

"He has no choice."

"He has your Great Bird, Leonardo."

"Then Lorenzo can fly it. Perhaps he will suffer the same fate as Tista. Better yet, he should order Andrea to fly it. After all, Andrea had it built it for him."

"Leonardo...."

"It killed Tista.... It's not safe."

"I'll tell Lorenzo you're ill," Sandro said.

"Send Niccolo back to me. I forbid him to—"

But Sandro had already left the studio, closing the large inlaid door behind him.

Exhausted, Leonardo leaned upon the table and imagined that he had followed Sandro to the door, down the stairs, and outside. There he surveyed his canvass- covered makeshift workshop. The air was hot and stale in the enclosed space. It would take weeks working alone to complete the new soaring machine. Niccolo should be here. Then Leonardo began working at the cordage to tighten the supporting wing surfaces. This machine will be safe, he thought; and he worked, even in the dark exhaustion of his dreams, for he had lost the ability to rest.

Indeed he was lost.

In the distance he could hear Tista. Could hear the boy's triumphant cry before he fell and snapped his spine. And he heard thunder. Was it the shouting of the crowd as he, Leonardo, fell from the mountain near Vinci? Was it the crowd cheering the Palio riders racing through the city? Or was it the sound of his own dream-choked breathing?

"Leonardo, they're going to fly your machine."

"What?" Leonardo asked, surfacing from deep sleep; his head ached and his limbs felt weak and light, as if he had been carrying heavy weights.

Francesco stood over him, and Leonardo could smell the man's sweat and the faint odor of garlic. "One of my boys came back to tell me...as if I'd be rushing into crowds of cutpurses to see some child die in your flying contraption." He took a breath, catching himself. "I'm sorry, Maestro. Don't take offense, but you know what I think of your machines."

"Lorenzo is going to demonstrate my Great Bird now?"

Francesco shrugged. "After his brother won the Palio, Il Magnifico announced to the crowds that an angel would fly above them and drop Hell's own fire from the sky. And my apprentice tells me that inquisitore are all over the streets and are keeping everyone away from the gardens near Santi Apostoli."

That would certainly send a message to the Pope; the church of Santi Apostoli was under the protection of the powerful Pazzi family, who were allies of Pope Sixtus and enemies of the Medici.

"When is this supposed to happen?" Leonardo asked the foreman as he hurriedly put on a new shirt; a doublet; and calze hose, which were little more than pieces of leather to protect his feet.

Francesco shrugged. "I came to tell you as soon as I heard."

"And did you hear who is to fly my machine?"

"I've told you all I know, Maestro." Then after a pause, he said, "But I fear for Niccolo. I fear he has told Il Magnifico that he knows how to fly your inventions."

Leonardo prayed he could find Niccolo before he came to harm. He too feared that the boy had betrayed him, had insinuated himself into Lorenzo's confidence, and was at this moment soaring over Florence in the Great Bird. Soaring over the Duomo, the Baptistry, and the Piazza della Signoria, which rose from the streets like minarets around a heavenly dome .

But the air currents over Florence were too dangerous. He would fall like Tista, for what was the city but a mass of jagged peaks and precipitous cliffs.

"Thank you, Francesco," Leonardo said, and, losing no time, he made his way through the crowds toward the church of Santi Apostoli. A myriad of smells delicious and noxious permeated the air: roasting meats, honeysuckle, the odor of candle wax heavy as if with childhood memories, offal and piss, cattle and horses, the tang of wine and cider, and everywhere sweat and the sour ripe scent of perfumes applied to unclean bodies. The shouting and laughter and stepping-rushing-soughing of the crowds were deafening, as if a human tidal wave was making itself felt across the city. The whores were out in full regalia, having left their district which lay between Santa Giovanni and Santa Maria Maggiore; they worked their way through the crowds, as did the cutpurses and pickpockets, the children of Firenze's streets. Beggars grasped onto visiting country villeins and minor guildesmen for a denari and saluted when the red carroccios with their long scarlet banners and red, dressed horses passed. Merchants and bankers and wealthy guildesmen rode on great horses or were comfortable in their carriages, while their servants walked ahead to clear the way for them with threats and brutal proddings.

The frantic, noisy streets mirrored Leonardo's frenetic inner state, for he feared for Niccolo; and he walked quickly, his hand openly resting on the hilt of his razor-sharp dagger to deter thieves and those who would slice open the belly of a passer-by for amusement.

He kept looking for likely places from which his Great Bird might be launched: the dome of the Duomo, high brick towers, the roof of the Baptistry...and he looked up at the darkening sky, looking for his Great Bird as he pushed his way through the crowds to the gardens near the Santi Apostoli, which was near the Ponte Vecchio. In these last few moments, Leonardo became hopeful. Perhaps there was a chance to stop Niccolo...if, indeed, Niccolo was to fly the Great Bird for Lorenzo.

Blocking entry to the gardens were both Medici and Pazzi supporters, two armies, dangerous and armed, facing each other. Lances and swords flashed in the dusty twilight. Leonardo could see the patriarch of the Pazzi family, the shrewd and haughty Jacopo de' Pazzi, an old, full-bodied man sitting erect on a huge, richly carapaced charger, His sons Giovanni, Francesco, and Guglielmo were beside him, surrounded by their troops dressed in the Pazzi colors of blue and gold. And there, to Leonardo's surprise and frustration, was his great Eminence the Archbishop, protected by the scions of the Pazzi family and their liveried guards. So this was why Lorenzo had made his proclamation that he would conjure an angel of death and fire to demonstrate the power of the Medici...and Florence. It was as if the Pope himself were here to watch.

Beside the Archbishop, in dangerous proximity to the Pazzi, Lorenzo and Giuliano sat atop their horses. Giuliano, the winner of the Palio, the ever handsome hero, was wrapped entirely in silver, his silk stomacher embroidered with pearls and silver, a giant ruby in his cap; while his brother Lorenzo, perhaps not handsome but certainly an overwhelming presence, wore light armor over simple clothes. But Lorenzo carried his shield, which contained "Il Libro," the huge Medici diamond reputed to be worth 2,500 ducats.

Leonardo could see Sandro behind Giuliano, and he shouted his name; but Leonardo's voice was lost in the din of twenty thousand other voices. He looked for Niccolo, but he could not see him with Sandro or the Medici. He pushed his way forward, but he had to pass through an army of the feared Medici-supported Companions of the Night, the darkly-dressed Dominican friars who held the informal but hated title of inquisitore. And they were backed up by Medici sympathizers sumptuously outfitted by Lorenzo in armor and livery of red velvet and gold.

Finally, one of the guards recognized him, and he escorted Leonardo through the sweaty, nervous troops toward Lorenzo and his entourage by the edge of the garden.

But Leonardo was not to reach them.

The air seemed heavy and fouled, as if the crowd's perspiration was rising like heat, distorting shape and perspective. Then the crowds became quiet, as Lorenzo addressed them and pointed to the sky.

Everyone looked heavenward.

And like some gauzy fantastical winged creature that Dante might have contemplated for his Paradisio, the Great Bird soared over Florence, circling high above the church and gardens, riding the updrafts and the currents that swirled invisibly above the towers and domes and spires of the city. Leonardo caught his breath, for the pilot certainly looked like Niccolo; surely a boy rather than a full-bodied man. He looked like an awkward angel with translucent gauze wings held in place with struts of wood and cords of twine. Indeed, the glider was as white as heaven, and Niccolo—if it was Niccolo—was dressed in a sheer white robe.

A Man-lifting Cody, similar to a late model Da Vinci design.

The boy sailed over the Pazzi troops like a bird swooping above a chimney, and seasoned soldiers fell to the ground in fright, or awe, and prayed; only Jacopo Pazzi, his sons, and the Archbishop remained steady on their horses. As did, of course, Lorenzo and his retinue.

And Leonardo could hear a kind of buzzing, as if he were in the midst of an army of cicadas, as twenty thousand citizens prayed to the soaring angel for their lives as they clutched and clicked black rosaries.

The heavens had opened to give them a sign, just as they had for the Hebrews at Sinai.

The boy made a tight circle around the gardens and dropped a single fragile shell that exploded on impact, throwing off great streams of fire and shards of shrapnel that cut down and burned trees and grass and shrub. Then he dropped another, which was off mark, and dangerously close to Lorenzo's entourage. A group of people were cut down by the shrapnel, and lay choking and bleeding in the streets. Fire danced across the piazza. Horses stampeded. Soldiers and citizens alike ran in panic. The Medici and Pazzi distanced themselves from the garden, their frightened troops closing around them like Roman phalanxes. Leonardo would certainly not be able to get close to the First Citizen now. He shouted at Niccolo in anger and frustration, for surely these people would die; and Leonardo would be their murderer. He had just killed them with his dreams and drawings. Here was truth. Here was revelation. He had murdered these unfortunate strangers as surely as he had killed Tista. It was as if his invention now had a life of its own, independent of its creator.

As the terrified mob raged around him, Leonardo found refuge in an alcove between two buildings and watched his Great Bird soar in great circles over the city. The sun was setting, and the high, thin cirrus clouds were stained deep red and purple. Leonardo prayed that Niccolo would have sense enough to fly westward, away from the city, where he could hope to land safely on open ground; but the boy was showing off and underestimated the capriciousness of the winds. He suddenly fell, as if dropped, toward the brick and stone below him. He shifted weight and swung his hips, trying desperately to recover. An updraft picked him up like a dust devil, and he soared skyward on heavenly breaths of warm air.

God's grace.

He seemed to be more cautious now, for he flew toward safer grounds to the west...but then he suddenly descended, falling, dropping behind the backshadowed buildings; and Leonardo could well imagine that the warm updraft that had lifted Niccolo had popped like a water bubble.

So did the boy fall through cool air, probably to his death.

Leonardo waited a beat, watching and waiting for the Great Bird to reappear. His heart was itself like a bird beating violently in his throat. Niccolo.... Prayers of supplication formed in his mind, as if of their own volition, as if Leonardo's thoughts were not his own, but belonged to some peasant from Vinci grasping at a rosary for truth and hope and redemption.

Those crowded around Leonardo could not guess that the angel had fallen...just that he had descended from the Empyrean heights to the man-made spires of Florence where the sun was blazing rainbows as it set; and Lorenzo emerged triumphantly. He stood alone on a porch so he could be seen by all and distracted the crowds with a haranguing speech that was certainly directed to the Archbishop.

Florence is invincible.

The greatest and most perfect city in the world.

Florence would conquer all its enemies.

As Lorenzo spoke, Leonardo saw, as if in a lucid dream, dark skies filled with his flying machines. He saw his hempen bombs falling through the air, setting the world below on fire. Indeed, with these machines Lorenzo could conquer the Papal States and Rome itself; could burn the Pope out of the Vatican and become more powerful than any of the Caesars.

An instant later Leonardo was running, navigating the maze of alleys and streets to reach Niccolo. Niccolo was all that mattered. If the boy was dead, certainly Lorenzo would not care. But Sandro...surely Sandro....

There was no time to worry about Sandro's loyalties.

The crowds thinned, and only once was Leonardo waylaid by street arabs who blocked his way. But when they saw that Leonardo was armed and wild and ready to draw blood, they let him pass; and he ran, blade in hand, as if he were being chased by wild beasts.

Empty streets, empty buildings, the distant thunder of the crowds constant as the roaring of the sea. All of Florence was behind Leonardo, who searched for Niccolo in what might have been ancient ruins but for the myriad telltale signs that life still flowed all about here, and soon would again. Alleyways became shadows, and there was a blue tinge to the air. Soon it would be dark. A few windows already glowed tallow yellow in the balconied apartments above him.

He would not easily find Niccolo here. The boy could have fallen anywhere; and in grief and desperation, Leonardo shouted his name. His voice echoed against the high building walls; someone answered in falsetto voce, followed by laughter. But then Leonardo heard horses galloping through the streets, heard men's voices calling to each other. Lorenzo's men? Pazzi? There was a shout, and Leonardo knew they had found what they were looking for. Frantic, he hurried toward the soldiers, but what would he do when he found Niccolo wrapped in the wreckage of the Great Bird? Tell a dying boy that he, Leonardo, couldn't fly his own invention because he was afraid?

I was trying to make it safe, Niccolo.

He found Lorenzo's Companions of the Night in a piazza surrounded by tenements. They carried torches, and at least twenty of the well-armed priests were on horseback. Their horses were fitted out in black, as if both horses and riders had come directly from Hell; one of the horses pulled a cart covered with canvass.

Leonardo could see torn fustian and taffeta and part of the Great Bird's rudder section hanging over the red and blue striped awning of a balcony. And there, on the ground below was the upper wing assembly, intact. Other bits of cloth slid along the ground like foolscap.

Several inquisitore huddled over an unconscious figure.

Niccolo.

Beside himself with grief, Leonardo rushed headlong into the piazza; but before he could get halfway across the court, he was intercepted by a dozen Dominican soldiers. "I am Leonardo da Vinci," he shouted, but that seemed to mean nothing to them. These young Wolves of the Church were ready to hack him to pieces for the sheer pleasure of feeling the heft of their swords.

"Do not harm him," shouted a familiar voice.

Sandro Botticelli.

He was dressed in the thick, black garb of the inquisitore. "What are you doing here, Leonardo? You're a bit late." Anger and sarcasm was evident in his voice.

But Leonardo was concerned only with Niccolo, for two brawny inquisitore were lifting him into the cart. He pushed past Sandro and mindless of consequences pulled one of the soldiers out of the way to see the boy. Leonardo winced as he looked at the boy's smashed skull and bruised body—arms and legs broken, extended at wrong angles—and turned away in relief.

This was not Niccolo; he had never seen this boy before.

"Niccolo is with Lorenzo," Sandro said, standing beside Leonardo. "Lorenzo considered allowing Niccolo to fly your machine, for the boy knows almost as much about it as you."

"Has he flown the Great Bird?"

After a pause, Sandro said, "Yes...but against Lorenzo's wishes. That's probably what saved his life." Sandro gazed at the boy in the cart, who was now covered with the torn wings of the Great Bird, which, in turn, was covered with canvass. "When Lorenzo discovered what Niccolo had done, he would not allow him near any of your flying machines, except to help train this boy, Giorgio, who was in his service. A nice boy, may God take his soul."

"Then Niccolo is safe?" Leonardo asked.

"Yes, the holy fathers are watching over him."

"You mean these cutthroats?"

"Watch how you speak, Leonardo. Lorenzo kept Niccolo safe for you, out of love for you. And how have you repaid him...by being a traitor?"

"Don't ever say that to me, even in jest."

"I'm not jesting, Leonardo. You've failed Lorenzo...and your country, failed them out of fear. Even a child such as Niccolo could see that."

"Is that what you think?"

Sandro didn't reply.

"Is that what Niccolo told you?"

"Yes."

Leonardo would not argue, for the stab of truth unnerved him, even now. "And you, why are you here?"

"Because Lorenzo trusts me. As far as Florence and the Archbishop is concerned, the angel flew and caused fire to rain from Heaven. And is in Heaven now as we speak." He shrugged and nodded to the inquisitore, who mounted their horses.

"So now you command the Companions of the Night instead of the divine power of the painter," Leonardo said, the bitterness evident in his voice. "Perhaps we are on different sides now, Little Bottle."

"I'm on the side of Florence," Sandro said. "And against her enemies. You care only for your inventions."

"And my friends," Leonardo said quietly, pointedly.

"Perhaps for Niccolo, perhaps a little for me; but more for yourself."

"How many of my flying machines does Lorenzo have now?" Leonardo asked, but Sandro turned away from him and rode behind the cart that carried the corpse of the angel and the broken bits of the Great Bird. Once again, Leonardo felt the numbing, rubbery sensation of great fatigue, as if he had turned into an old man, as if all his work, now finished, had come to nothing. He wished only to be rid of it all: his inventions, his pain and guilt. He could not bear even to be in Florence, the place he loved above all others. There was no place for him now.

And his new soaring machine.

He knew what he would do.

Leonardo could be seen as a shadow moving inside his canvass-covered makeshift workshop, which was brightly lit by several water lamps and a small fire. Other shadows passed across the vellum-covered windows of the surrounding buildings like mirages in the Florentine night. Much of the city was dark, for few could afford tallow and oil.

But Leonardo's tented workshop was brighter than most, for he was methodically burning his notes and papers, his diagrams and sketches of his new soaring machine. After the notebooks were curling ash and smoke rising through a single vent in the canvass, he burned his box-shaped models of wood and cloth: kites and flying machines of various design; and then, at the last, he smashed his partially completed soaring machine...smashed the spars and rudder, smashed the box-like wings, tore away the webbing and fustian, which burned like hemp in the crackling fire.

As if Leonardo could burn his ideas from his thoughts.

Yet he could not help but feel that the rising smoke was the very stuff of his ideas and invention. And he was spreading them for all to inhale like poisonous phantasms.

Lorenzo already had Leonardo's flying machines.

More children would die....

He burned his drawings and paintings, his portraits and madonnas and varnished visions of fear, then left makeshift studio like a sleepwalker heading back to his bed; and the glue and fustian and broken spars ignited, glowing like coals, then burst, exploded, shot like fireworks or silent hempen bombs until the canvass was ablaze. Leonardo was far away by then and couldn't hear the shouts of Andrea and Francesco and the apprentices as they rushed to put out the fire.

Niccolo found Leonardo standing upon the same mountain where Tista had fallen to his death. His face and shirt streaked with soot and ash, Leonardo stared down into the misty valley below. There was the Palazzo Vecchio, and the dome of the Duomo reflecting the early morning sun...and beyond, created out of the white dressing of the mist itself, was his memory cathedral. Leonardo gazed at it...into it. He relived once again Tista's flight into death and saw the paintings he had burned; indeed, he looked into Hell, into the future where he glimpsed the dark skies filled with Lorenzo's soaring machines, raining death from the skies, the winged devices that Leonardo would no longer claim as his own. He wished he had never dreamed of the Great Bird. But now it was too late for anything but regret.

What was done could not be undone.

"Maestro!" Niccolo shouted, pulling Leonardo away from the cliff edge, as if he, Leonardo, had been about to launch himself without wings or harness into the fog. As perhaps he was.

"Everyone has been frantic with worry for you," Niccolo said, as if he was out of breath.

"I should not think I would have been missed."

Niccolo snorted, which reminded Leonardo that he was still a child, no matter how grown up he behaved and had come to look. "You nearly set Maestro Verrocchio's bottega on fire."

"Surely my lamps would extinguish themselves when out of oil, and the fire was properly vented. I myself—"

"Neighbors saved the bottega," Niccolo said, as if impatient to get on to other subjects. "They alerted everyone."

"Then there was no damage?" Leonardo asked.

"Just black marks on the walls."

"Good," Leonardo said, and he walked away from Niccolo, who followed after him. Ahead was a thick bank of mist the color of ash, a wall that might have been a sheer drop, but behind which in reality were fields and trees.

"I knew I would find you here," Niccolo said.

"And how did you know that, Nicco?"

The boy shrugged.

"You must go back to the bottega," Leonardo said.

"I'll go back with you, Maestro."

"I'm not going back." The morning mist was all around them; it seemed to be boiling up from the very ground. There would be rain today and heavy skies.

"Where are you going?"

Leonardo shrugged.

"But you've left everything behind." After a beat, Niccolo said, "I'm going with you."

"No, young ser."

"But what will I do?"

Leonardo smiled. "I would guess that you'll stay with Maestro Verrochio until Lorenzo invites you to be his guest. But you must promise me you'll never fly any of his machines."

Niccolo promised; of course, Leonardo knew that the boy would do as he wished. "I did not believe you were afraid, Maestro."

"Of course not, Nicco."

"I shall walk with you a little way."

"No."

Leonardo left Niccolo behind, as if he could leave the past for a new, innocent future. As if he had never invented bombs and machines that could fly. As if, but for his paintings, he had never existed at all.

Niccolo called to him...then his voice faded away, and was gone.

Soon the rain stopped and the fog lifted, and Leonardo looked up at the red tinged sky.

Perhaps in hope.

Perhaps in fear.

Inspired by Da Vinci designs my Uncle drew a lifesize outline of the craft on the floor of the studio and from that the machine grew into an over fifteen-foot wingspan glider capable of supporting a man--OR a young boy like myself--in flight. I am not sure what his exact plan for the machine was, but one day without my uncle's knowledge a friend of mine and I hauled it out of the studio and up to the top of the second story apartments across the compound, and hanging on for dear life, launched it.

Initially the flight played out fairly well, picking up wind under the wings and maintaining the same twostory height advantage for some distance. Halfway across busy Arlington Street though, the craft began slowing and losing forward momentum. It began dropping altitude rapidly, eventually crashing into the porch and partway through the front windows of the house across the way. Other than a few bruises and a wrecked machine, nothing was broken, although as it turned out, my dad wasn't nearly as proud of me as intended. I never forgot the thrill of that flight and carried that thrill and Leonardo's dreams into my adulthood.(see)

The Obeah poured a warm tea-like broth into two small bowl-shaped cups without handles. He took one and gave me the other, gulping down the liquid while motioning me to do the same. (see)

He asked me what I liked about Jamaica. I told him things like the weather and the people. Then he asked again what I liked about Jamaica. But now I wasn't able to answer. It was like my mind had grown so huge that trying to focus on something as minuscule as a few words to string together into a sentence had become an impossible hardship. As I struggled to form something at least semi-comprehensible the Obeah asked, "What about the old man in a far away place a long time ago that constructed bird-like contraptions in order to fly even as you did as a child?" Da Vinci was the answer, but I couldn't form the words. Finally I told him about my Totem Animal, the huge wingspan condor-like vultures the Jamaicans call John Crows, that glide and soar for hours, riding the thermals and never flapping their wings.

That the Obeah seemed to like. Soon a cool breeze fell across my face even though it came from a direction from across the fire. The Obeahman took a vessel of water and tossed it onto the flames. A huge cloud of steam burst forth followed by a thick cloud of smoke. I jumped back and turned away, stumbling to the ground while covering my face and eyes. Then it got cold, very cold. The breeze began to blow harder and I could no longer feel the ground underneath me. It felt as though I was moving very fast, yet as far as I knew I was still on the ground by the fire. I moved my arm away from my face just barely squinting my eyes open. For an instant I was still in the billowing white smoke, then suddenly I broke through to clean, fresh air. The smoke was no longer smoke, but clouds high in the night sky. I wasn't on the ground, but hundreds of feet in the air, soaring through the night, arms along my side, wind in my face, stars over my head.

With absolutely no effort I was able to swoop down the darkened mountain gullies and high into the air, eventually passing above Bamboo Lodge recognizable along the mountain road even in the dark because of a large empty in those days, swiming pool. Then, just barely above the treetops I picked up speed and headed toward the lighted streets and tall buildings of New Kingston. Soon I was even higher in the air over Port Royal, Lime Cay, and the Caribbean. Then somehow the exhilaration began to fade. I turned back toward the mountains as a creeping apprehension seeped into my thoughts. Then nothing.

Around ten the next morning a couple of Jamaican kids found me unconscious in a ravine about a mile from Bamboo Lodge and miles from the Obeah's hut, naked, all scratched up, and in the bushes, as though I had crashed through the trees or something. The kids apparently went to their parents or adults and told them there was a naked whiteman in the gully all beat up. Since I was one of the few whitemen in the area the adults must have assumed it was me and told Benji, the Bamboo Lodge groundskeeper. After discovering for sure who it was, he brought some shoes and clothes and took me home. Everybody in the village area knew what had happened.

The above paragraphs of the Wanderling's flight has been extrapolated from the following. For the complete story please click the image:

Dann, Jack: "Da Vinci Rising"

*****

*****

Comments: This story is an revised and expanded version of an excerpt from Dann's THE MEMORY CATHEDRAL: A Secret History of Leonardo da Vinci, Bantam 1995 (0553096370), Easton 1996, Bantam 1996 (0553378570), HarperCollins Australia/Flamingo 1998 (0732259517). And while this story is alternate history, instead, as the subtitle indicates, a secret history (i.e., after Leonardo burned his books, drawings, machines, etc.).

LEONARDO

DA VINCI

Webring

Maintained by:

the Wanderling